By María Carmen Martín Palacios

In the context of modern geopolitics, maritime dominance has become one of the main battlefields for XXI century superpowers. Historically, Asia has been the region that has witnessed more conflicts related to water sovereignty, and even today there are ongoing disputes over the control of certain maritime areas, such as the Spratly Islands. The reasoning behind these conflicts is not only the supervision of a strategic region, but also the access to valuable natural resources such as gas or coal. Consequently, the resolution of maritime disputes entails a superlative diplomatic effort, which may sometimes leave behind a sense of grievance among the countries involved in the contest. However, there are exceptions to this rule, as proved with the East-Timor/Australian dispute, which has been set to an end with the signature of a definitive accord over the conflict of the Timor Sea.

Historical Background

Since its independence from Indonesia, East-Timor has become an essential actor in Southeast Asia. This small country had been under the dominance of the Portuguese Empire until the year 1975, when the Revolutionary Front for an Independent East Timor resistance movement declared independence. However, the new country was soon invaded by Indonesia as they feared of a contagious insurrectional effect over its territories on the western part of the island of Timor. Consequently, the country was administrated by Indonesia until the year 2002, when it relinquished the control of East-Timor following the United Nations sponsored act of self-determination.

Australian/East-Timor relationship

Source: (Cook, 2017), New dawn on Greater Sunrise energy dispute; obtained from http://www.atimes.com/article/new-dawn-greater-sunrise-energy-dispute/

However, the new nation had to face a severe humanitarian crisis, as the presence of Indonesian forces in the territory had left behind over 100,000 casualties and numerous inhabitants living under the poverty line. Australia was then one of the largest country donors, as it led international aid packages. Moreover, its assistance was not only focused in poverty alleviation, but it also provided the country with technical guidance aimed at building key capacities that will ensure good governance practices. Thereby, the initial relationship between both countries was smooth and supportive.

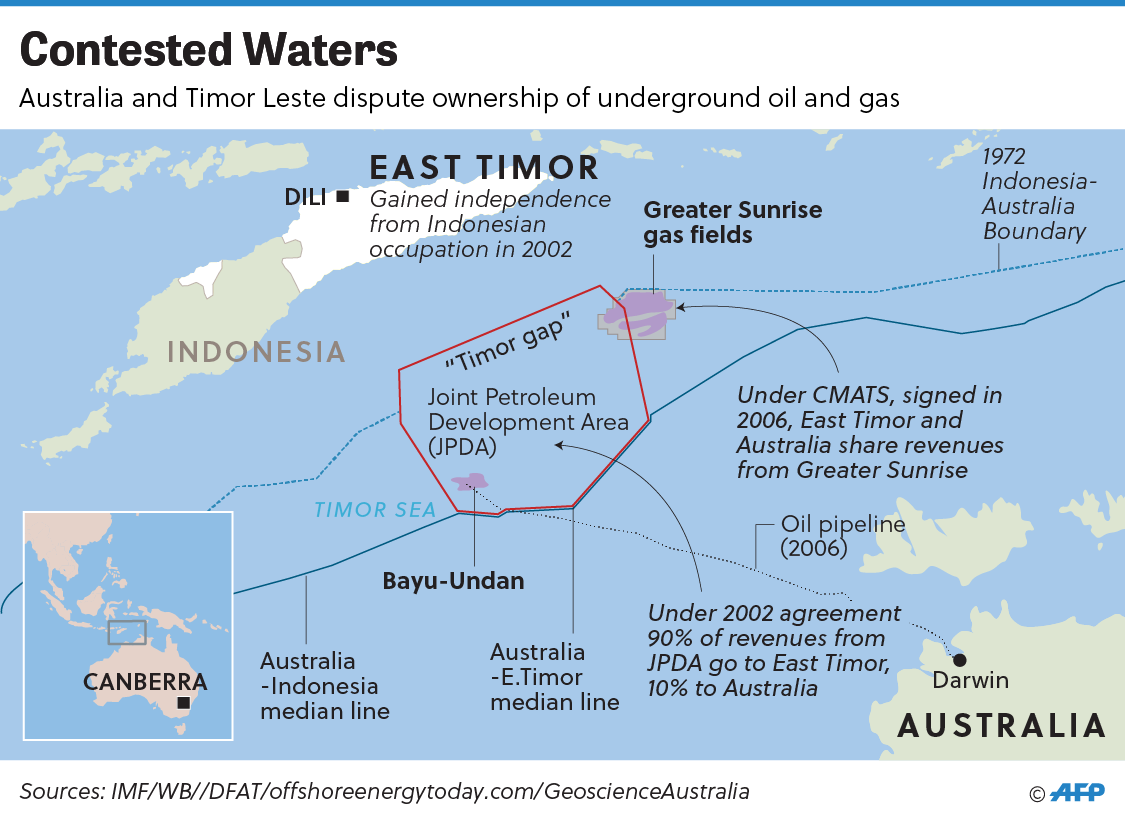

Nonetheless, in the last years these bilateral relations have worsened, due to the maritime dispute over the Timor Sea. This territory is the natural separation of both countries as it is bounded to the north by Timor-Leste and to the South by Australia. The discovery of oil in the 1970´s gave rise to a legal battle over the control of the territory, aimed at safeguarding the exclusive exploitation of these natural resources. The difficulty of these conflict is that the area which is the richest in petroleum lies in between the Australian-East-Timor border, known as the “Timor Gap.”

During the Indonesian administration of East-Timor, there was a temporary accord over the control of the territory, whose terms were abandoned following the independence of Timor-Leste. Even though both countries showed their willingness to solve the dispute with the 2002 Timor Sea Treaty, this agreement was not sufficient to address the demands of extension of their sovereign waters, and was limited to the economic administration of petroleum-related activities.

On one hand Australia demanded to extend the line of greatest sea-bed-depth, a petition which clashed with Timor-Leste´s claim of readopting the maritime boundaries during the Portuguese presence in the island (which were accorded under the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea).

In the last decade, both parties have sought to set an end to this maritime disaccord, by seeking external mediators that could help both parties to reach a common ground. However, and as minor agreements took place, both countries agreed to demand The Permanent Court of Arbitration to mediate in the dispute, showing their true commitment to cease hostilities. As a result, in September both parties signed an agreement that tackled the legal status of the gas fields, establishing a special regime for its administration, which is an advancement towards the definitive solution of the conflict.

Conclusion

Even though it is still soon to analyze the outcomes of the new Australian-Timor-Leste agreement, what is certain is that this accord proves that ceasing historical disputes is possible when the parties involved show a true commitment to resolve their misunderstandings. Nonetheless, we will see in the upcoming months if both parties respect the terms of the agreement or if their territorial aspirations overcome their diplomatic effort.

María Carmen Martín Palacios is a senior studying Business Administration and International Relations at the University of Pontificia Comillas (Madrid, Spain).

Sources

Cotton, J. (2004). East Timor, Australia and regional order: intervention and its aftermath in Southeast Asia (Vol. 10). Routledge.

Devia Garzón, C. A., & Cadena Afanador, W. R. (2012). EAST TIMOR: INTERNATIONAL INTERVENTION AND MARITIME DEMARCATION. Revista de Relaciones Internacionales, Estrategia y Seguridad, 7(2), 53-74.

Esposito, C. D. (1996). The East Timor Issue before the International Court of Justice. Anuario de Derecho Internacional, 12, 617.

Nevins, J. (2004). Contesting the boundaries of international justice: state countermapping and offshore resource struggles between East Timor and Australia. Economic Geography, 80(1), 1-22.

Schofield, C. (2007). Minding the gap: the Australia–East Timor Treaty on certain maritime arrangements in the Timor Sea (CMATS). The International Journal of Marine and Coastal Law, 22(2), 189-234.